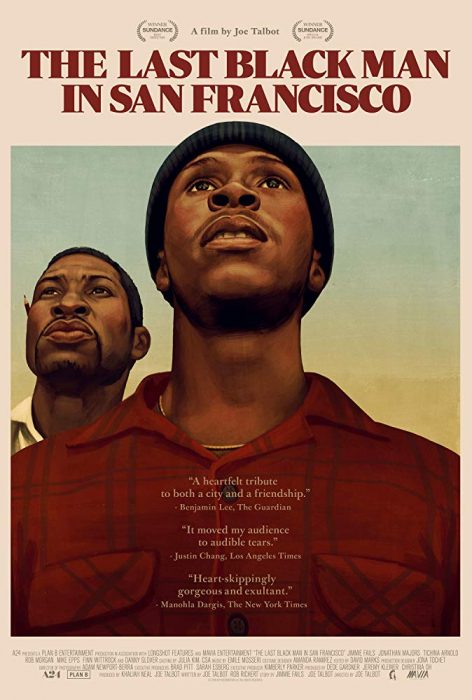

Lyrical and poignant, The Last Black Man in San Francisco takes a deceptively simple premise and infuses it with deep emotion and moments of pure visual poetry. Themes of longing, loss, memory and friendship run through the film, which centers on 20-something San Francisco native Jimmy Fails (first-time actor Jimmie Fails, portraying a fictionalized version of himself), who yearns to reclaim the beautiful, if now somewhat dilapidated, Victorian mansion that he lived in as a child. It was the only place he ever felt safe and secure. The house sits in San Francisco’s historic Fillmore District where, starting in the second half of the 19th Century, waves of immigrants – first Jews from Europe, then Japanese, then African-Americans from the deep South – moved in, seeking jobs and an escape from racism and discrimination. Once a bastion of African-American culture and a vibrant center for jazz, the Fillmore District and its diverse culture fell victim to city officials who, complaining of crime and urban blight, redeveloped the area in the 1970s, forcing out lower-income residents. Gentrification attracted wealthy white buyers and displaced the predominantly black residents, many of whom felt their removal was the reason behind the revitalization effort.

Lyrical and poignant, The Last Black Man in San Francisco takes a deceptively simple premise and infuses it with deep emotion and moments of pure visual poetry. Themes of longing, loss, memory and friendship run through the film, which centers on 20-something San Francisco native Jimmy Fails (first-time actor Jimmie Fails, portraying a fictionalized version of himself), who yearns to reclaim the beautiful, if now somewhat dilapidated, Victorian mansion that he lived in as a child. It was the only place he ever felt safe and secure. The house sits in San Francisco’s historic Fillmore District where, starting in the second half of the 19th Century, waves of immigrants – first Jews from Europe, then Japanese, then African-Americans from the deep South – moved in, seeking jobs and an escape from racism and discrimination. Once a bastion of African-American culture and a vibrant center for jazz, the Fillmore District and its diverse culture fell victim to city officials who, complaining of crime and urban blight, redeveloped the area in the 1970s, forcing out lower-income residents. Gentrification attracted wealthy white buyers and displaced the predominantly black residents, many of whom felt their removal was the reason behind the revitalization effort.

Jimmie has had no permanent home since his family was forced out of the house when he was six years old. Everybody scattered; his mother abandoned him and, for a while, Jimmie and his father bounced around between homeless shelters, housing projects and living in a car. The two hardly ever see one another now. Jimmie has been crashing on the bedroom floor of his best friend Montgomery (Jonathan Majors), who lives in his grandfather’s (Danny Glover) modest house. An artist and aspiring playwright, the intellectual “Mont” works as a fishmonger during the day. Jimmie takes care of patients in a senior care facility. The two men share an unusually close emotional bond – a platonic love that is rarely seen in movies.

The look of longing in Jimmie’s eyes says everything there is to know about this quiet young man, who skateboards past his former home almost every day. When the older white couple who live there lose their lease, Jimmy and Montgomery move in and set out to restore the place to its former glory. The idyll doesn’t last long, however, as the house is soon up for sale – with a four-million-dollar price tag.

An air of wistful melancholy hangs over the film, in keeping with its dream-like quality. Despite the hazardous waste sign on the beach and the man in a hazmat suit picking up trash, urban blight has never looked so benign, bathed in shimmering light and muted, golden hues. The breath-taking cinematography is by Adam Newport-Berra; the beautiful, haunting score by Emile Mosseri. Both Fields and Morgan are superb, giving intensely intimate performances. The film marks the feature debut of director Joe Talbot, Field’s real-life best friend since childhood.

The film is both an ode to San Francisco and a rumination on a particular black experience (Morgan is white). A gentleness permeates the film, helping to soften the ugliness and hardship all around. Drunks and derelicts appear in a kind of slow-motion ballet. A man drifts by on a skateboard, a little girl skips down a sidewalk, also both in slow-motion. A man standing on a box pleads to anybody who will listen, “this is our home!” This small, heartfelt film wowed audiences at the Sundance Film Festival, where Talbot picked up the Best Director Award and the film won a Dramatic Special Jury Prize for creative collaboration.