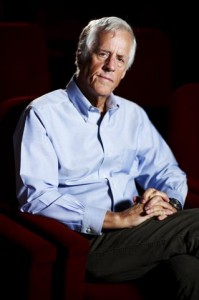

Director Michael Apted sat down with film critic Jean Oppenheimer, on behalf of Writers Bloc Presents to talk about 56 Up, the latest installment in his groundbreaking documentary series. He started the conversation by confessing, “I never know what the new film is going to be until I see it with an audience.”

WritersBlocpresents.com: Not even while editing it?

Michael Apted: I know each individual life but, until I see the completed film with an audience and it becomes a shared experience, I can’t sense the tone of the whole thing. We had a screening with about 100 people last May and it was a revelation to me [in that I found the] film so very positive. Despite all the economic crises we have all been living through, these people, especially those who have invested their lives in their families and not their careers, have a real solid base for their lives.

WB: Even Jackie, despite the many hardships she has had to endure, reports that she still sees the glass half-full, not half-empty.

Apted: I agree. Recently I was interviewed by Terry Gross for Fresh Air and she felt that Jackie’s life has been terribly painful for her — and that Symon seems very unhappy. I didn’t get that sense from either Jackie or Symon, but I think that’s the power of the series: people project themselves onto it. It’s the drama of everyday life. We are watching something we have all shared in. One thing that did surprise me was I thought people would be looking towards old age more than they were.

WB: You asked Paul about getting old and he said, “but I don’t really feel like I am.”

Apted: Well, I’m certainly beginning to panic!

WB: About what?

Apted: About the future! I’m 72 years old. I’m not worried about dying but, rather, having a decent exit, as it were –- whether work will dry up. I’m concerned whether I’m going to have enough resources to be able to have a retirement and whether I’m going to enjoy retirement because I have always worked. I have never had a hobby. Those sorts of things.

WB: You are mentioning two separate issues: finances and what we do to occupy ourselves. You know, you don’t have to retire.

Apted: It’s more that I shall get retired; people will stop offering me jobs at some point. At 72 I think about that more and was surprised –- agreeably surprised — that, at age 56, the Up participants didn’t. Perhaps 56 is too young to be panicking. I wonder if they will when they get a bit older.

WB: Some of the questions you ask these people are very personal –- most un-British. Is it difficult for you to ask them?

Apted: Sometimes painfully so. I can’t bring myself to ask if they are still having sex.

WB: But I like how you phrase it — whether the couple still has chemistry. It’s obvious what that means.

Apted: (laughing) Yes; it’s obvious to them, too. I think I need to ask certain things, though. If I don’t ask, people will say, “why didn’t you?” I panic when I have to ask a leading question. I think “should I do it now? Will I wreck the whole interview? Will they get upset?” I also don’t ask everybody the same questions. I know some people will clam up if I do. For example, I don’t think I could ask something very intimate of Suzy.

WB: I thought filming her and Nick together worked out well.

Apted: Yes, and it was their idea. Suzy said, “I’ll do it but I want to do it with Nick.”

WB: How did you feel about the conversation they had, in which they discussed the series itself?

Apted: It was completely spontaneous on their part; I didn’t ask anything. Nick lead the conversation and I thought what they said was great. Suzy seemed so much more relaxed [sharing the stage] with Nick.

WB: You were a researcher at Granada Television when Seven Up, the first of the films, was made. How did you choose the children?

Apted: We wanted to choose kids from different social backgrounds. I was [sent to] the East End of London. I rang up the local Educational Authority and asked whether they could recommend schools. I then rang up the schools and asked whether they were willing to take part. If they were, I’d show up, meet the teachers and tell them to, “bring me out your likeliest candidates.” By that I did not mean the smartest kids, but the ones who wouldn’t be intimidated by having ten people standing in a room all staring at them.

We weren’t interested in their characters but, rather, as sort of symbols of the class they came from. The questions we asked were very simple and straightforward. We didn’t vet or audition them. I just went, ‘you, you and you,’ although I must admit that when I met Tony [who wanted to be a jockey and became a cab driver] I thought, ‘oh, I do want him.’

WB: Did you need to get parental permission?

Apted: No. It sounds outrageous now but none of that happened in those days. We never had a contract with any of them, never got parental permission. We probably got verbal agreements and, certainly, the schools agreed, but it was all very loosey-goosey. Life was simpler in those days; television was simpler. It wasn’t so threatening; it didn’t have the kind of repercussion it does today.

WB: Seven Up was intended as a stand-alone program. How did you convince Granada to make it into a series?

Apted: It’s a strange story. Seven Up was very popular — and then nothing happened. Five years later I was sitting in the commissary at Granada. I was now a much bigger cheese; I had worked my way through the system and was directing a lot of dramas. And the head of Granada came in and sat down beside me and said, “Have you ever thought of going back and seeing what has happened to them?” And I said, “no, but how interesting.” So that’s what happened. I always say that 7 PLUS SEVEN wasn’t very good; at age 14 the kids were spotty and monosyllabic. But you could see there was the beginning of a big idea. I’ll never forget the critical response; it was out of all proportion, as though I had invented the wheel. Here was television being used in a slightly different way. It was a no-brainer to keep the series going.

It wasn’t until 21 Up that we discovered a lot of residual anger in some of them about being in the series –- because they had had no say in it. They felt kind of railroaded into it. In fact, one of them, Charles Furneaux, dropped out after 21 Up. And just last time Jackie told me, “you got me wrong; you didn’t present me in the right way.” Yet, despite any misgivings she might have, she and the others are still here. When people look at the series in generations to come, what it will tell them about the second half of the 20th century in the United Kingdom I don’t know.

WB: What do you think it says about Britain?

Apted: Some good things. Had I started it 10 or 20 years later, it would have been different. It wouldn’t have been quite so alarming. But I do believe it’s still there: the curse, the shadow of your birth still hangs over what people’s options are.

WB: I didn’t get the sense that some of the participants realize that. Perhaps those in the upper class are more conscious of that.

Apted: Oh, I think Tony always was. He came to New York when the film opened two weeks ago and we did Q&As together. He said, “When I was seven, I knew I didn’t have nothing. I knew that whatever I was going to get I was going to have to fight for.” And he did say that in earlier programs. But, no, I don’t think they all realized that.

WB: Paul seems to know that he could have pushed himself more, but he seems happy. Have you found a different level of self-reflection among the classes?

Apted: Some of them just don’t give me much, particularly the posh boys. Andrew and John are wonderfully nice, personable, decent men; I like them both very much but they aren’t very forthcoming.

WB: Do you think it’s tied to their upper class status?

Apted: I think so. As the ruling class you don’t want to open yourself up to much, to reveal too much.

WB: What is your own background? I believe you were a scholarship student.

Apted: My father was in fire insurance; my mother was a homemaker. I loved my mother but we had a fairly combative relationship that, quite frankly, I don’t think I have ever recovered from. She came from an interesting generation of women. She was very, very smart, the youngest of six, had three children, and it was inconceivable that she would ever work. She looked after her aging parents until she got married; as the youngest child, it was her duty to do so. She never really exercised the gifts she had or the intelligence she had, and she was very frustrated and angry about it. And she realized it. It’s why she wanted me to make absolutely the best I could of my life. I was the oldest of three. I was ‘the golden boy’ and always had to step up. She was always pushing, pushing, pushing; she felt I never did enough.

WB: She felt you didn’t achieve enough? I don’t understand how you could have been more successful.

Apted: My parents were absolutely mortified when I got a job in television. They wanted me to be a solicitor. I was the first in my entire family to go to Oxbridge [the combined nickname for Oxbridge and Cambridge Universities; Apted attended Cambridge]. I was one of the first in my family to even go to university! And then I pissed it away in their eyes by doing Coronation Street. It took them ten years to figure out I had a proper job. Fortunately they did before they died.

WB: How did you first get interested in filmmaking?

Apted: I was interested in entertainment from an early age. I loved to listen to the radio. I learned to read by reading the radio times. My mother loved the music hall; she loved the entertainment business. I loved doing school plays and at 16 I saw [Ingmar Bergman’s] Wild Strawberries and knew what I wanted to do. I never thought I’d ever have the opportunity to do it. I had a few lucky breaks; going to Granada at that time was huge.

Commercial television was fairly young, staffed with people from the BBC, journalism, theatre and the film industry. Early on they wanted to start creating a first generation of television people. They would go to Oxbridge and recruit people. They would take 30 or 40 students up to Manchester and put them through an intensive, two-day round of interviews and pick six of them. [Director] Mike Newell is a contemporary of mine and we both got in on that course and had exactly the same career.

WB: Getting back to the Up series, I was surprised that no one has died or been gay.

Apted: I get told off all the time for not having more women [but in 1964, when we started, that wasn’t in the public consciousness the way it is today]. We also were missing big chunks of the middle class. We went to the extremes — the East End of London and Kensington — but what about that whole world in-between? Well, the Liverpool boys, Peter and Neil, were in that in-between world. Neil’s disappointment when he didn’t get into Oxford was terrible. He acknowledges having some sort of psychological issues but has always refused to get medical attention. The producers of the series did take some trouble to figure out if we were damaging him by putting him through the interviews, but we were told that if he wants to do it, he should do it. And he is a wonderful interview!

WB: I felt the upper crust kids had expectations for themselves, put there by their parents. What were the expectations for the working class kids?

Apted: I don’t think they had any. The only ones who were really secure about their future prospects were the really posh boys, who declared at the age of seven, “I’m going to this school and read law.” The Neils and Nicks of this world wanted to be train drivers or astronauts –- just what I would have said if I had been asked at seven. Only the upper class had a real grip on what was possible.

WB: And what would be available to them. A friend asked me to ask you whether the series has produced any academic analyses about class and gender issues, race, or determinism vs. free will?

Apted: I’m sure it has, but I wouldn’t know what. I show up at academic conferences when invited. I was asked to go to Harvard’s School of Sociology and screen 42 Up. I was petrified, even though everybody was very nice to me. I did go through a period of about half-an-hour when I thought, “I’d better learn about all this.” I actually bought a book about sociology, read about a page of it and thought, “this is ridiculous; stop it! You make films, you are quite good at interviewing people, you know who these people are, and you are the ordinary man in the street. People aren’t watching this because you are knowledgeable, so just stop it!”

WB: Do you ask the same questions of each person?

Apted: No. I have learned that each of them has to be different. I try and just have a conversation. I don’t know where it might go; I just try to be freewheeling. I used to try and predict things, which is always a disaster. When Tony was 21 he was hanging out at the dog track; I was convinced he’d be in the slammer by the age of 28. I had this brilliant idea for 21 Up — to have him drive me around the East End of London in his cab, pointing out the hot spots of crime. I thought it would make good material for 28 Up, when I was sure he’d be in prison.

It didn’t work out that way, of course, and it was embarrassing. I actually implied to him that he would end up in trouble –- and he knew I was implying it. I remember him telling me, “Michael, don’t judge a book by its cover.” So I stopped myself from having emotional expectations about how each would turn out. I gave up being God.

WB: Maybe Tony would have ended up in prison if he had never met you. You don’t know how your interaction with these people might have affected them.

Apted: I don’t think they see enough of me to have that kind of effect. I’m not that present; I only see them every seven years. Besides, they deny that it has ever changed their lives and I accept what they say.

WB: What has touched you most about the series?

Apted: It’s how each individual has coped with certain things. It sounds so pompous but it really is those heroic, little things that they do: the decisions they take about their children or the troubles they have to overcome — like Tony having to bring up his granddaughter or Jackie overcoming what appears to be impossible odds, or some of them losing parents. Those are the things I find so moving.