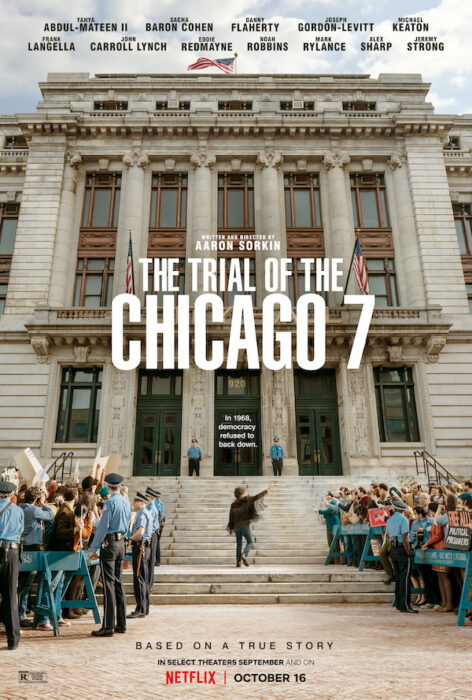

For those old enough to remember the actual events – and perhaps even for those too young to have been alive at the time – The Trial of the Chicago 7 is tremendous fun. The subject matter itself could not be more serious, depicting a volatile time in the United States when the nation was torn apart by deep political and cultural divisions.

Written and directed by Aaron Sorkin, the film opens with a montage of archival footage from the late 1960s: President Lyndon Johnson announcing he is increasing troop levels in Vietnam; TV news reports from the war zone, showing American soldiers burning Vietnamese huts; student protests rocking US campuses and cities; the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy; an enraged Mayor Richard Daley and thousands of Chicago police and National Guardsmen in full riot gear. The montage ends with CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite declaring, “the Democratic Convention is about to begin in — there doesn’t seem to be any other way to say it — a police state.”

The convention took place in August, 1968. While hewing closely to historical facts, Sorkin takes more than a few liberties with the official record (a few made-up, albeit minor, characters; some added dialogue), but the overall film remains faithful to the insanity that unfolded in Chicago before, during and after the Democratic National Convention, when law enforcement and antiwar demonstrators clashed on the streets of Chicago.

The majority of the film takes place inside an Illinois District Circuit courtroom in which, nearly a year after the events occurred, eight defendants were put on trial for conspiracy to cross state lines in order to incite violence. The eight defendants represented different antiwar factions; some of whom had never even met before the trial began. Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne) and Rennie Davis (Alex Sharp) were the clean-cut leaders of the non-violent Students for a Democratic Society; Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohn) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong) represented the Youth International Party (better known as the Yippies), merry pranksters known primarily for their copious consumption of drugs and ribald antics in and out of court; and pacifist David Dellinger (John Carroll Lynch), 20 years older than his co-conspirators. Defendants John Froines (Daniel Flaherty) and Lee Weiner (Noah Robbins) were practically unknown to the general public — college professors who had little to do with the mayhem that erupted. The eighth defendant was Bobby Seale (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), the head of the Chicago Black Panthers, who had nothing to do with the protests; he just happened to be in Chicago that day to give a talk. The Nixon administration hoped his presence would frighten jury members. Half-way through the trial, he successfully lobbied to separate his case from the others.

Representing seven of the defendants – all but Bobby Seale, whose own lawyer was in the hospital — were William Kunstler (Mark Rylance) and Leonard Weinglass (Ben Shenkman). Prosecuting the case on behalf of the US government was Assistant US Attorney Richard Schultz (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) who never sought the assignment and had strong reservations about the Federal government’s case. The Johnson Administration, in power at the time of the convention, had decided not to bring charges against the men but, when Richard Nixon assumed the presidency, he and his Attorney General, John Mitchell (John Doman), opened a case for the express purpose of nailing the defendants to the cross and cowing other antiwar activists. The presiding judge was the cantankerous, antagonistic unabashedly partisan Julius Hoffman (Frank Langella).

In addition to the courtroom proceedings the film highlights the antipathy between Hayden and Abbie Hoffman, whom Hayden considered a clown, not really invested in the cause. Thanks to a nuanced and highly convincing performance by Baron Cohen, Hoffman’s commitment to stopping the war Is not in doubt. Acting is good across the board, even if some of the real-life participants might quibble with their depictions. Dialogue is always one of Sorkin’s strengths. When not adhering to the trial’s transcript, he adds some memorable lines. One of the best is when Froines turns to Weiner and questions how the two of them ended up on trial in such illustrious company. Replies Weiner, “Think of it like the Oscars; it’s an honor just to be nominated.”

Nixon and Mitchell may have thought the prosecution would dissuade future antiwar activity, but it was really the defendants who put the government on trial. The Trial of the Chicago 7 is a slice of history that needs to be told, especially given the fraught political environment in which we find ourselves today, but despite the seriousness and grave importance of the subject matter, the film proves entertaining as hell.