Half the books I purchase come from perusing the obituary pages of The New York Times. It’s rarely the familiar names that pique my interest: the accomplished scientists, artists, academics and business leaders who received recognition during their lifetimes. Rather, it’s the other half that sparks my curiosity: the obscure, never-heard-of-them-before people who made remarkable but largely unheralded contributions to history. Moe Berg was one of those individuals.

Never a household name, except to perhaps a handful of baseball enthusiasts, Berg was a man of multiple talents, numerous contradictions and a closet full of closely-guarded secrets. He was a jigsaw puzzle whose pieces never fit together. A linguist who graduated magna cum laude from Princeton, he played Major League Baseball for 15 seasons (studying philology at the Sorbonne and earning a law degree from Columbia University during the sport’s off-seasons). “He could speak a dozen languages but couldn’t hit in any of them,” quipped one teammate. Batting was never his forte but he was a solid enough catcher and short-stop to be signed by four different ball clubs. He started his career with the Brooklyn Dodgers and ended it with the Boston Red Sox.

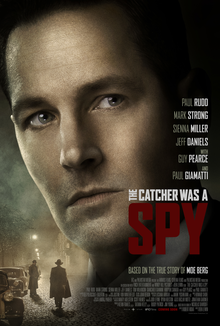

Berg’s baseball career might have earned him a couple of short paragraphs in The Times obit section, but it was his pivotal role serving in the OSS (the Office of Strategic Services) both before and during World War II that cemented his place in history. Even today some of the files on his undercover activities remains classified. Maybe The Catcher Was a Spy, directed by Australian Ben Lewin, will finally bring Berg the attention he deserves – probably the last thing this exceedingly private man would have wanted.

Based on Nicholas Dawidoff’s 1995 book The Catcher was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg, the film is a combination character study and espionage thriller — and it works well on both levels. (An earlier biography, co-written by Louis Kaufman, Barbara FitzGerald and Tom Sewell, was published in 1975, three years after Berg’s death.) Brimming with atmosphere and suspense, the film opens on a foggy street in Zurich, Switzerland in 1944. It’s nighttime. Sodium vapor street lamps at the far end of the road turn the heavy mist yellow. Two men stand in the foreground, barely visible in the dark. As they talk, the scene cuts back and forth between this set-up and the same two men sitting inside a café earlier in the evening. The conversation is sobering, heightening the sense of tension and danger and sucking the viewer in (the excellent screenplay is by Robert Rodat, who also penned Saving Private Ryan, while the moody, deep-focus cinematography is by Andrij Parekh). The action then jumps back eight years to Berg’s time with the Red Sox.

Paul Rudd is completely – and rather surprisingly — convincing as the enigmatic Berg. Best known for his work in comedies, the actor possesses an innate likeability and an expression somewhere between naivety and befuddlement. With a subtle but significant modification in performance, those same qualities serve him well in The Catcher Was a Spy. His eyes and facial muscles change just enough to suggest a highly focused mind behind a still amiable mien. Interestingly, his gaze also reflects a certain sadness, suggesting a self-awareness that he didn’t fit in anywhere. Although he had a long-term love affair with piano teacher Estella Huni (an achingly believable Sienna Miller), there are suggestions Berg also may have had gay liaisons.

Casting recognizable actors in key roles can sometimes be so distracting it takes you out of the film. This is not a problem with Rudd, Miller or Guy Pearce, who portrays US Army Major Robert Furman, chief of foreign intelligence for the atomic bomb project. Berg’s most significant mission, and the centerpiece of the film, was to track down German physicist Werner Heisenberg (the always reliable Mark Strong) and determine how close the Nazis were to making their own nuclear weapon. Paul Giamatti and Jeff Daniels play other significant but minor roles in the film. Unfortunately, they do not fare as well. Although both are solid actors, for some reason it is harder to suspend disbelief with them.

One of the big ironies of Berg’s life was his ability to meld into almost any setting. His affability and his facility with languages – apparently with no discernible American accent – allowed him to come across as a kind of everyman in any country he visited. As the film makes abundantly clear, however, Berg was anything but ordinary.