An air of poetry hangs over Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, a film that echoes both Days of Heavens and Bonnie and Clyde in its elegiac visual beauty and its mythological feel for rural America. Although set in the early 1970s — in Texas, like the other two pictures (though all three were shot predominantly in other locations) — the film has the same Depression-era look and atmosphere as its predecessors — and the same eye for plain-spoken, inchoate characters whose restless spirits push them to tempt fate.

An air of poetry hangs over Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, a film that echoes both Days of Heavens and Bonnie and Clyde in its elegiac visual beauty and its mythological feel for rural America. Although set in the early 1970s — in Texas, like the other two pictures (though all three were shot predominantly in other locations) — the film has the same Depression-era look and atmosphere as its predecessors — and the same eye for plain-spoken, inchoate characters whose restless spirits push them to tempt fate.

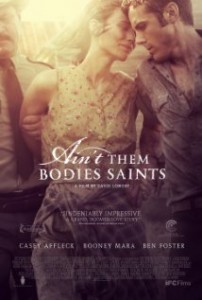

Bob (Casey Affleck) and Ruth (Rooney Mara) are the young outlaw couple, in love and fiercely loyal to one another. A robbery gone awry sends Bob to prison; Ruth is spared incarceration when Bob takes the fall for her shooting of a deputy (an equally excellent Ben Foster). Bob’s letters home are filled with longing for Ruth and their baby daughter, as well as intimations of escape and eventual reunion. The shy deputy, Patrick, occasionally checks in on Ruth and her daughter. He clearly has a crush on her but is too gentlemanly to push his case. Ruth’s feelings for him are more difficult to gauge, contributing to a growing sense of tension, especially when Bob makes his escape and heads back to claim his wife and daughter. Writer-director David Lowery’s beautifully crafted script unfolds as if guided by fate, with no hints of which direction the story will go or how it will end.

Ain’t Them Bodies Saints excels at creating a sense of place, both geographic and psychological. Shot on celluloid –- and relying as much as possible on natural light or low–level practicals, (primarily lamps) — the movie is sometimes so dark it’s difficult to make out what’s on screen, but the reliance on ambient light adds a layer of authenticity that mirrors the uncertainties of the unfolding plot. The moody cinematography is by Bradford Young, who picked up the 2013 Sundance Award for Best Cinematography for his work on both this film and Mother of George.

Mara, Affleck and Foster are all superb — as is Nate Parker as Sweetie, Bob’s saloon-keeper friend who shelters him when he escapes from prison, and Keith Carradine as Bob and Ruth’s surrogate father. Dialogue is spare and plainspoken and no excuses are offered for wayward behavior. “We did what we did and that’s who we are,” says Bob after his arrest. Silence is just as important as talking in this low-key, noir-tinged tale, serving as a testament to the outwardly impassive, but deeply felt inner, lives of its characters. Daniel Hart’s score is by turns bluesy, reflective and haunting.