Four men hanging out in a motel room, crossing swords philosophically, may not sound like the makings of a great film, but One Night in Miami is one of the most profound, significant and engaging films of the year. It captures an actual moment in U.S. history: the time when black consciousness was on the rise among African-Americans and differing opinions over how best to confront racism and achieve social, political and economic equality strained even close relationships.

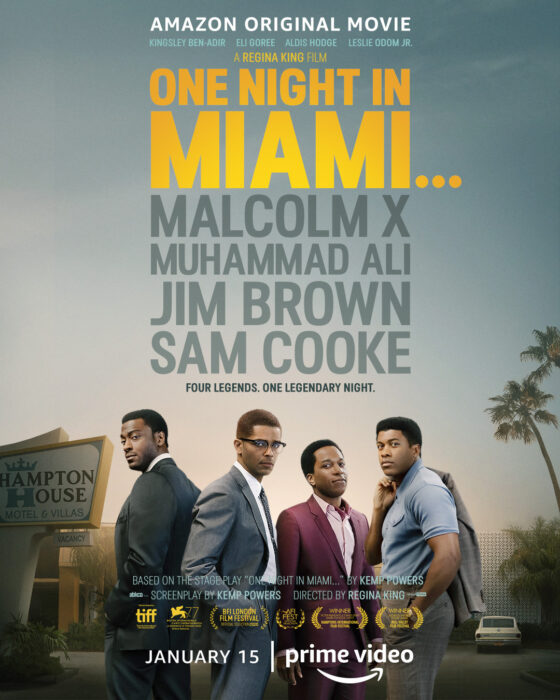

Half-fact and half-conjecture, the film takes place on the night of February 25, 1964, when a cocky, 22-year old boxer named Cassius Clay defeated Sonny Liston to become the new heavyweight champion of the world. Clay (Eli Goree), who would soon adopt the name Muhammad Ali, celebrates his victory with three of his closest friends: legendary football player Jim Brown (Aldis Hodge), soul singer/songwriter Sam Cooke (Leslie Odom, Jr.), and black nationalist/Nation of Islam spokesman Malcolm X (Kingsley Ben-Adir). With his victory over Liston that night, Clay enters their ranks as a black cultural icon.

The four men meet at The Hampton House Motel, where Malcom X is staying. In the Jim Crow South, blacks weren’t allowed to rent hotel rooms in Miami Beach, where the title match was held; the Hampton House in nearby Brownsville had become the place for famous black entertainers and politicians to stay. Clay, Brown and Cooke are looking forward to a night on the town, but Malcolm has something more serious on his mind. He wants to impress upon his friends how important it is that they use their fame and success to further the cause of the burgeoning African-American civil rights movement.

It so happens that each man is at a pivotal point in his life. Clay has just skyrocketed to the top of the sports world and, with Malcolm as his spiritual guide, is about to announce his conversion to Islam and his embrace of the Black Muslim movement. Unbeknownst to Clay, however, Malcolm is secretly planning to leave the Nation of Islam and form a separate Black Nationalist party. He has become bitterly disillusioned with Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad. Malcolm expects that Clay will follow him, raising the profile of the new organization. Jim Brown, meanwhile, has been cast in his first movie role and is considering retiring from football to pursue a full-time acting career. Cooke has his own decisions to make, as he carves out a place for himself in the white-dominated music industry.

This is the point at which the movie shifts from actual events to speculation. Screenwriter Kemp Powers, adapting his own 2013 stage play, imagines the conversation that might have ensued that night. The greatest tension in the movie stems from the conflict between Cooke and Malcolm, who accuses the popular crooner of pandering to white audiences with his pop-infused love songs, instead of “using your voice to help your own people.” Malcolm puts Bob Dylan’s “Blowing in the Wind” on the phonograph and asks how it is that a white boy from Minnesota is writing the kind of protest songs that Cooke ought to be releasing.

The argument becomes increasingly heated and personal. “You’re nothing but a wind-up toy,” taunts Malcolm. Cooke counters, “I want to spread my message [to all audiences]. We can’t go out and start declaring white people devils.” Upset by the mounting hostility, Brown tries to lower the temperature, pointing out that “If we are to be free, we have to be economically free. And Sam is!”

One Night in Miami excels on every level. It marks the auspicious feature directorial debut of Academy Award-winning actress Regina King, who elicits strong performances from her ensemble cast and, with the help of cinematographer Tami Reiker, keeps the camera constantly but unobtrusively moving. Set predominantly in one-room, the film never feels stage-bound — in contrast to Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, which hones closely and deliberately to its theatrical roots.

Powers’ dialogue is impressive: intelligent, humorous, contemplative, witty and substantive. Odom, Hodge, Goree and Ben-Adir never make a false move, creating four distinct personalities. The camaraderie among the characters is palpable, as are the conflicts. This is a movie that is concerned with both ideas and personalities — and it has the ring of truth throughout.

Perhaps the most potent — and certainly the most disturbing – moment in the film comes near the beginning, when Brown stops off in his hometown of St. Simons Island, Georgia at the invitation of a long-time white acquaintance who wants to congratulate him on leading the Cleveland Browns to victory. The scene will shock and horrify white audiences; black viewers will be outraged but not surprised. It is a gut-wrenching example of what life was like for blacks in the segregated South — and throughout much of America. Nor has that war yet been won, making this film as timely as it is important.