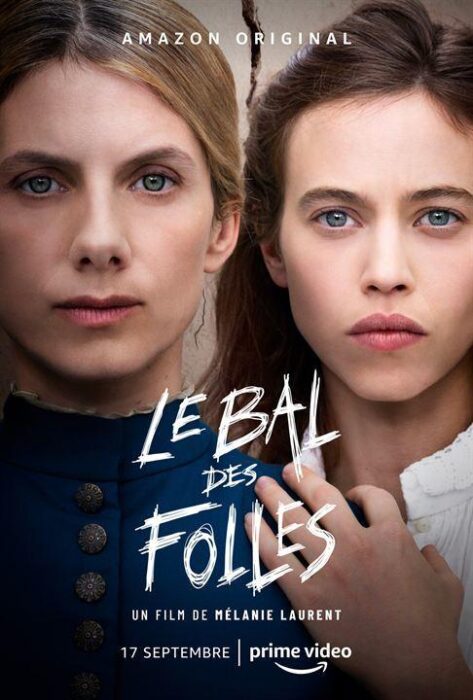

The French period drama “Le Bal des Folles” (“The Mad Women’s Ball”) is an exquisitely-made film on every level: acting, direction, script, production design, cinematography, costumes, editing and score. Adapted from an historical novel by Victoria Mas, the movie confronts the stigmatization of women in late 19th Century Paris and the heavily circumscribed role permitted them in a male-dominated society. Troublesome wives, women who did not conform to their family’s or society’s expectations of them, the indigent and the mentally or physically disabled often were simply dumped at Paris’ Salpetriere Neurological Clinic (a euphemism for insane asylum) where they might languish for decades. Making the film even more harrowing is that Salpetriere was—and still is — a real place and many of the events described in the film actually happened. Director Mélanie Laurent, who also co-wrote and co-stars in the picture, populates the film with both fictional characters and real-life figures who played prominent roles in the incidents depicted. Chief among them are Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot (Grégoire Bonnet), a neurologist who pioneered the use of hypnosis on his vulnerable patients.

The mesmerizing young actress Lou de Laage (“The Innocents,” “White as Snow”) is riveting as Eugénie Cléry, a fictional character who stands in for all of the real women who were diagnosed with “acute symptomatic hysteria” and locked away in the hospital. Unlike most of the patients, Eugénie is a member of the upper class and her domineering father commits her to the asylum when he learns that she believes she sees and speaks with the spirits of the dead. Indeed, Eugenie is visited by spirits. Wisely, however, Laurent does not give these spirits physical form – no shimmering, ghostly shapes to confirm their presence — and, while Eugenie speaks aloud to the spirits, only she can hear their voices.

“The Mad Women’s Ball” opens on the nape of a woman’s neck. The camera follows her as she joins thousands of mourners gathered for Victor Hugo’s funeral. This is Eugénie, but we do not see her face until she slips into her family’s dining room, late for dinner. The 26-year old beauty has backbone and grit, a great love of literature and a passion for the outdoors. While she tries to adhere to her parent’s wishes, she chafes under society’s proscribed role for young women of her social standing.

A short time later the camera again picks up the back of a woman’s head as she is walking. It is a mirror image of the opening shot, but the woman is not Eugénie, but Genevieve, the senior nurse at Salpetriere. When not working she cares for her father, a man of science who, like Eugénie’s father, totally rejects the spiritual. When we first meet her, it isn’t clear if she will be a sympathetic character or not, especially as she is responsible for executing Dr. Charcot’s orders. But Genevieve is haunted by the death of her beloved younger sister, Blandine. One day, Blandine appears to Eugénie with a message for Genevieve. The fates of nurse and patient are now and forever inextricably bound.

The title of the film comes from an actual ball that the hospital threw every year. The patients dressed up in costumes and were allowed to mingle with high society types who had been invited to gape at the inmates. One of the many strengths of the film is how Laurent has structured the script to enhance its thriller aspects, as well as tying characters to one another. Cross-cutting reveals Eugénie and Genevieve in different locations as each rips off their layers of suffocating corsets and underclothes. Each is desperate to at least be free from the constraints binding their bodies. The second effective use of cross-cutting comes at the end of the film, as two separate and fraught events play out at the same time —both races against time.

The story behind the Salpetriere Hospital is as intriguing as the film itself, but most viewers will be unaware that the setting, the general story and several of the characters are based on historical fact. Dr. Charcot was famous throughout Europe for his use of hypnosis and the violent convulsions it caused in some patients. Physicians and visitors would travel to Paris to sit in on these demonstrations. Although it is not mentioned in the film, Sigmund Freud was one of those who attended these sessions and was heavily influenced by Charcot’s approach.

The film is visually sumptuous, especially those sections that take place in the Cléry family’s exquisitely appointed household. Cinematographer Nicolas Karakatsanis is heavily influenced by art and many of his shots resemble gorgeous, still paintings. Lit only by natural sources – candles, oil lamps — these scenes exude a warmth, beauty and sense of privilege that contrasts sharply with the white, overly bright dormitory at the asylum and the lines of laundry the patients are responsible for washing. White sheets are strung across the room by the open windows, drying in the sunshine.

Laurent, perhaps best known in the US for her acting roles in such films as “Inglorious Bastards,” “Operation Finale” and “The Roundup,” has directed numerous films, often ones with a strong point of view. One of the strengths of “Le Bal des Folles” is that, without any overt attempt to draw a comparison, the film puts on trial not only the rigid, social and cultural mores of the 1880s but, by implication, the continuation of many of these same attitudes and strictures today.