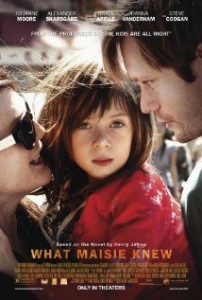

At the age of six, actress Onata Aprile is already a formidable talent, able to hold her own against an emotionally ferocious performance by Julianne Moore in What Maisie Knew, the story of a child caught between her selfish, narcissistic, warring parents. Adapted from a Henry James’ novel, but updated to contemporary New York City, six-year old Maisie (Aprile) must navigate a volatile psychological landscape to find a place where she can feel protected and safe.

Moore portrays her fading rock star mother, clinging to whatever remnants of fame still remain, even though it requires her to be almost continuously away from her daughter. Steve Coogan plays the child’s father, an art dealer who initially seems more sympathetic but proves equally self-centered and irresponsible. Both Susanna and Beale love their daughter but in an almost abstract way; certainly neither makes any effort to spend time with her. The job of caring for Maisie falls to Margo (Joanna Vanderham), the youngster’s compassionate, twenty-something, Scottish nanny, who makes the mistake of marrying Beale soon after his divorce from Susanna. In retaliation, Susanna impetuously marries Lincoln (Alexander Skarsgard) a handsome bartender/band hanger-on 20 years her junior.

Awarded joint custody, both parents all but abandon Maisie, leaving her in the care of Margo and, increasingly, the ill-prepared Lincoln, who unexpectedly rises to the occasion, growing in maturity before our very eyes. Like the novel, the film is told from Maisie’s perspective. Without ever losing her childlike purity or naturalness, she progresses from innocence to understanding to a place of wisdom that guarantees a measure of safety and happiness, while also allowing her to love and forgive her dysfunctional parents.

A lifelong bachelor, with no children of his own, James possessed a remarkable ability to get inside the minds of the young –- and, as in the case of Maisie, very young –- characters who populate many of his stories. And he couldn’t have found a better interpreter for his singular insight than Aprile who, in her feature film debut, commands the screen with ever-watchful eyes, a knowing stillness and an almost preternatural emotional intelligence that helps Maisie traverse the explosive minefield that is her parents’ disintegrating marriage.

The five lead actors are uniformly excellent. The always-accomplished Moore doesn’t shrink from presenting Susanna as the monstrously neglectful mother she is. Because we see her through Maisie’s eyes, however, we also detect a vulnerability that keeps her from becoming a totally hateful character. Skarsgard gives a surprisingly touching and utterly convincing performance as a young man drifting aimlessly through life, whose basic decency compels him to assume unsought responsibilities — and becomes a better human being because of it.

But it is Aprile, with those eyes that change imperceptibly yet speak volumes, who walks away with this film. Kudos also to directors Scott McGehee and David Siegel (the duo that made the excellent 2001 film The Deep End) for providing an environment in which Aprile could shine, and who keep the film from slipping into melodrama — an accomplishment that must be shared with screenwriters Nancy Doyne and Carroll Cartwright, who adapted the Henry James novel.

Also worth noting this week is the documentary Valentino’s Ghost, from writer/director Michael Singhwhich examines “the politics of images” –- specifically, how changing depictions of Arabs and Islam in films, television and the press color and reflect American perceptions and are even used to influence — or, perhaps more accurately, endorse — our government’s national and international policies in the Middle East. The Arab as smoldering heartthrob — most notably Rudolph Valentino in The Sheik silent films –- soon gave way to the Arab as barbarian and threat when Western economic and political interests in the region shifted with our growing thirst for oil. Valentino’s Ghost proves both informative and highly entertaining.