There are two cinematic “journeys” well worth taking this week. They each offer a window into history, art, drama and life itself, albeit within very different contexts.

There are two cinematic “journeys” well worth taking this week. They each offer a window into history, art, drama and life itself, albeit within very different contexts.

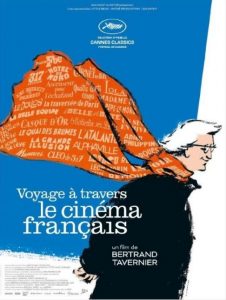

The enthralling My Journey Through French Cinema is 76-year old writer/director Bertrand Tavernier’s love-letter to Gallic movies and filmmakers, with a special emphasis on the 1930s and 40s. These were the films that both formed and transformed Tavernier, not only as a filmmaker but, equally importantly, as a human being.

Born in Lyon in 1941, Tavernier was a child of war. The city was liberated from the Nazis in 1944, but conditions under the occupation had caused serious damage to his health. Diagnosed with tuberculosis, he was confined to a sanatorium. The only entertainment was on Sundays, when films were projected for the patients. Tavernier, who was six when he saw his first film, said the discovery gave him a purpose in life: “They kept me alive.” Upon leaving the sanatorium, he was sent to boarding school where, if students kept up their grades, they were permitted to see movies at local theatres. It proved a great inducement to study.

Tavernier has never stopped watching movies. The passionate affair that began when he was six years old has lasted a lifetime, never losing its sacred hold on him. The “my” in the documentary’s title suggests this will be a very personal and intimate tour; Tavernier, who narrates the film when he isn’t serving as on-screen guide, confirms this almost immediately: “Making the documentary was a way of looking for my past.”

The director, whose own body of work includes A Sunday in the Country, Life and Nothing But and ‘Round Midnight, devotes extensive time to each of his subject’s, citing not just one or two of their films but surveying entire careers. He analyzes how their staging of a shot or scene through camera moves, lens size and angle, composition, movement of actors within the frame, depth of field, lighting, etc. is most important in terms of capturing emotional truths about the characters and story. The human element – the viewer’s ability to emotionally and psychologically connect with the characters – is the most vital component of any truly great film.

Although My Journey Through French Cinema is structured in a generally chronological order, it has a stream of consciousness feel to it; a scene, an actor, a piece of music triggers thoughts and anecdotes about other artists. Tavernier, who was a film critic and author before making his own directing debut in 1974, almost defiantly waits until the film’s final hour to even mention the French New Wave, which broke completely with the past and presented an entirely new paradigm concerning structure and story-telling.

He does not spare those whose films – or lives – have at times disappointed him. His subjects include revered names, such as Jean Renoir, Marcel Carné, Jacques Becker, Jean-Pierre Melville, and iconic French actors Jean Gabin and Yves Montand — as well as those whose names or prodigious output are known today by only the most ardent, knowledgeable cineastes. These include directors Edmond T. Gréville and Claude Sautet (along with Melville, a major influence on Tavernier), actors Eddie Constantine and Lino Ventura. He also pays homage to composers, signaling out Maurice Jaubert and Joseph Kosma. “Music,” remarks Tavernier, “goes in when words can no longer express emotion.”

Watching My Journey, with its hundreds of exquisite movie clips and Tavernier’s accompanying analyses – always in a conversational tone; never dry or academic — transports viewers into another world, just as that first film did for Tavernier when he was a child. The documentary’s three-hour and 10-minute running time flies by in the blink of an eye, leaving viewers euphoric, nostalgic and, perhaps most telling, hungering for more

The second film, titled simply The Journey, concerns Northern Ireland’s troubled past; specifically, the 2006 “St. Andrews Agreement” — a miracle, if ever there was one — that “ended” the devastating civil war that had racked Northern Ireland for more than four decades. “The Troubles” – a rather restrained term to describe 40-plus years of vitriolic hatred and bloodshed – was a conflict born of religious and cultural animosity and distrust (what might be termed “identity politics” today). It pitted the country’s Protestant majority, led by the fiery, self-righteous Reverend Ian Paisley, against the Catholic minority, who felt –- and were –treated as second-class citizens. The Protestants wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom; the Catholics desperately wanted to be absorbed into the Republic of Ireland.

The conflict claimed thousands of lives through bombings, assassinations and street violence that was carried out by both sides. Footage from the period attests to the daily brutality. A woman, interviewed at the time, describes the conflict as “a tit-for-tat war: Kill a Catholic; kill a Protestant.” (Although the infamous “Bloody Sunday” incident of 1972 is often cited as the start of The Troubles, the “Irish Problem” predated that by more than half-a-century.)

After years of failed attempts to reach a peace accord – and pressured by the governments of both England and Ireland — representatives of Northern Ireland’s two dominant political parties – the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), led by Paisley, and Sinn Féin, the political wing of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), led by Martin McGuinness (although his compatriot Gerry Adams was always far better known) — agreed to sit down together in St. Andrews, Scotland and try to hammer out an agreement that would end hostilities and create a power-sharing government.

The Journey does not purport to be a true account of what transpired during that meeting. That’s primarily because nobody seems to know what the two implacable foes actually said to one another – only that, by the end of it, an agreement had been reached. Director Nick Hamm acknowledges – in fact, stresses — in the film’s opening title that what audiences are about to see is not historically factual; it is a made-up drama, a speculative account of what might have gone on during the meeting. The characters are real; they did meet and, against all odds, they did broker a deal – a deal that is reflected accurately in the movie.

What Hamm and screenwriter Colin Bateman have added – have imagined – is the conversation between the two men, as well as the plot device that places them together in a van on the way to Glasgow Airport, so that Paisley can fly to Belfast for his 50th wedding anniversary. In the film the van trip is engineered by members of the British and Irish governments, including Prime Minister Tony Blair and his Irish counterpart, Bertie Ahern. A camera and recording device inside the van permits government officials, along with Paisley’s son and Gerry Adams, who are still in St. Andrews, to hear what the two men are saying to one another. This entire scenario is pure fiction.

What is factual, however, is that the two men did share a van and did fly with one another to Belfast – on the theory that opposing sides in a conflict must remain together, to ensure that neither man can be signaled out for assassination by the opposing faction. Apparently, the actual agreement was ironed out on that flight, rather than in the van (and even here historians disagree).

I always prefer my history straight-up – i.e. historically accurate – but I was willing to make an exception for The Journey for a variety of reasons: First, it is so beautifully acted, especially by Colm Meany as Martin McGuinness. Timothy Spall’s Ian Paisley seems to stray a bit into caricature, although the DUP leader reportedly was grim, disapproving and self-righteous. Toby Stephens is wonderful as a very anxious Tony Blair; in fact, all the supporting players acquit themselves admirably, even those in the somewhat thankless roles (John Hurt as the MI5 agent who concocted the ruse). Secondly, the film contains a great deal of humor, both situational and character-driven; gripping drama; palpable tension; and top-notch dialogue, witty but believable. Furthermore, the final outcome – an historically accurate, if most improbable, agreement — was, indeed, reached between the two sides, bolstering the belief (some would say fantasy) that a mutually agreeable solution can be achieved if people begin to see one another not as evil and malevolent, but as human beings with differing views.

“It’s not the destination but the journey that matters” is a keystone of many religious and secular philosophies. In the case of The Journey, it is the destination – the final result — that is of towering significance; the journey – the made-up bits about how the parties managed to arrive at that destination – is, for once, of less significance.