We are delighted to present another in a series of film reviews by film critic Jean Oppenheimer.

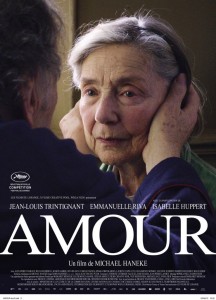

With Amour, Austrian-born writer/director Michael Haneke has crafted his masterpiece. An exquisite film, but not an easy one to watch, Amour –- in French, with English subtitles — concerns Georges and Anne (Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva, both superb), an octogenarian couple who are confronted with a devastating new reality when Anne suffers a debilitating stroke, followed by the first signs of dementia.

It is clear the couple shares an unusually loving and intimate bond, so bound up with one another that they have little room for their self-centered daughter (Haneke regular Isabelle Huppert). At first, Georges insists on taking care of Anne himself, but soon he is forced to hire nurses. Frustrated by her impaired condition, Anne lashes out verbally and physically. Shocked and distressed by his wife’s sudden change in personality, Georges watches helplessly and, at times, acts harshly. The dementia that slowly robs Anne of her senses is harrowing to watch, not only for Georges but for the movie audience as well. A profoundly unsentimental filmmaker, Haneke spares neither his characters nor his audience the indignities of Anne’s decaying body and mind.

An icy detachment has long informed Haneke’s work — less so in Amour than in his previous works. In fact, Amour is quite a departure for Haneke, who has always been a controversial filmmaker –- more for his earlier projects, Benny’s Video, Funny Games (both the Austrian and American versions), The Seventh Continent –- than for his more recent work, such as Caché and The White Ribbon. (The Piano Teacher, my favorite of his films after Amour, falls somewhere in-between.) Throughout his career the director has revealed what can only be described as a perverse, sadistic streak, not only toward the characters in his films but also toward the movie audience. He seems to relish implicating the viewer in the psychological violence that unfolds on screen, as if to say, “why are you willing to sit here and watch this unfathomable cruelty? What’s wrong with you?”

Haneke has been making films in France — and in French — for the past decade; the American version of Funny Games was his sole English-language endeavor. There is a meticulous, unflinching precision to all of his films. Working here at the pinnacle of his talent, Haneke has surprised both his admirers and his detractors, exhibiting a sense of human feeling absent from his other work. Despite the pain, suffering and shocking events that transpire on screen, Amour clearly is a film about a deep and enduring love. It is the most compassionate film Haneke has ever made.