Hannah Arendt was one of the 20th Century’s great intellectuals. A refugee from Nazi Germany, the political theorist (a description she preferred over “philosopher”) is perhaps best known for coining the phrase “the banality of evil” to describe Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi functionary responsible for implementing Hitler’s meticulously planned “Final Solution” of the Jews. Covering Eichmann’s 1961 trial in Jerusalem for The New Yorker (she was there just for the opening few weeks), Arendt was confounded by how completely ordinary the defendant appeared to be. She had expected to find a monster, someone to match the murderous deeds in which he had participated; instead, she found a man of utter “mediocrity,” someone totally unremarkable who, in choosing blind obedience to Hitler, had willingly forfeited his capacity for thinking and forming moral judgments of right and wrong.

Hannah Arendt was one of the 20th Century’s great intellectuals. A refugee from Nazi Germany, the political theorist (a description she preferred over “philosopher”) is perhaps best known for coining the phrase “the banality of evil” to describe Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi functionary responsible for implementing Hitler’s meticulously planned “Final Solution” of the Jews. Covering Eichmann’s 1961 trial in Jerusalem for The New Yorker (she was there just for the opening few weeks), Arendt was confounded by how completely ordinary the defendant appeared to be. She had expected to find a monster, someone to match the murderous deeds in which he had participated; instead, she found a man of utter “mediocrity,” someone totally unremarkable who, in choosing blind obedience to Hitler, had willingly forfeited his capacity for thinking and forming moral judgments of right and wrong.

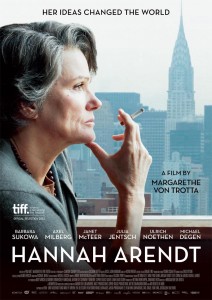

The biopic Hannah Arendt, directed by Margarethe von Trotta, covers a four-year period during which Arendt (a brilliant Barbara Sukowa) attended the trial and wrote her five-part series for The New Yorker (later published as a book under the title Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on The Banality of Evil). The movie focuses not only on the blowback from her controversial statements but also her relationship with her husband Heinrich Blucher (Axel Milberg) and her friendship with writer Mary McCarthy (Janet McTeer). The film touches briefly, via flashbacks, on her youthful love affair with philosopher Martin Heidegger.

Arendt was vilified by critics across the intellectual spectrum and renounced by some of her closest friends. Many people mistakenly believed she was labeling the atrocities themselves banal when, in fact, she was trying to juxtapose the atrocity of the deeds with the mediocrity of the man. It was “too simplistic, too abstract,” she claimed, to label Eichmann a monster. Many people felt she had been taken in by Eichmann’s calculatingly submissive and stumbling performance; others thought she was laying some of the blame on the Jews themselves. Although deeply stung by the loss of close friends, Arendt refused to defend herself, contending that what she meant was obvious.

Arendt was described by her friends as charming, warm and witty; her critics called her arrogant and abrasive. In Barbara Sukowa’s remarkable performance, the character exhibits all of these characteristics yet still proves sympathetic — reflecting von Trotta’s own perspective. Sukowa receives stellar support from McTeer and Nicholas Woodeson as New Yorker editor William Shawn.

The film makes masterful use of black-and-white, archival footage of the 1961 courtroom proceedings, showing judges, witnesses, and Eichmann himself, seated in a bullet-proof glass booth. It is unnerving to see the actual man, who truly does appear chillingly ordinary, and to witness his complete lack of remorse. An early scene of Shawn and two other magazine editors discussing the advisability of assigning Arendt to the trial (she had asked to cover it) is obviously inserted strictly to provide necessary background information for the viewer.

Hannah Arendt changed the discourse not only on the Holocaust but on evil itself by suggesting that individuals who choose not to exercise their ability to think and reason also abdicate their responsibilities as human beings to make moral judgments. Her thesis has gained adherents over the years but, due in part to her academic, unemotional way of addressing the issue, Arendt remains a polarizing figure to this day.