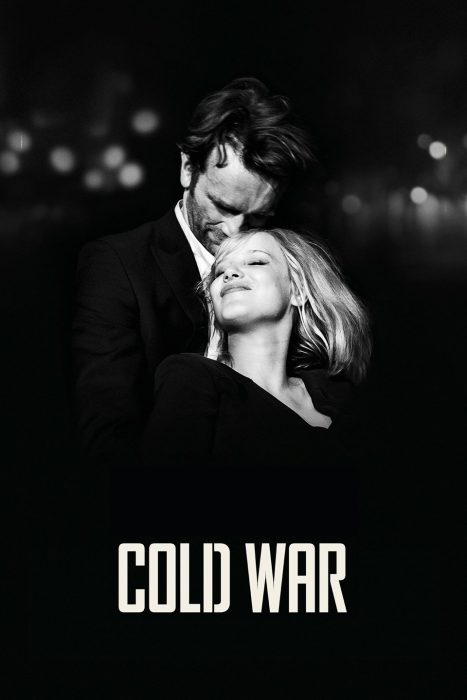

The intimate Polish drama Cold War charts a tempestuous love affair that plays out against the changing political landscape of post-World War II Europe. The title refers to both the geopolitical, ideological divide that arises after the war and the tensions that continually threaten the passionate but tumultuous relationship between the film’s mismatched lovers. Poland’s submission to the Oscars this year, Cold War has just been shortlisted by the Motion Picture Academy — one of only ten foreign-language films to make the cut. It also just walked off with the European Film Awards for best film, director, screenplay and actress.

The intimate Polish drama Cold War charts a tempestuous love affair that plays out against the changing political landscape of post-World War II Europe. The title refers to both the geopolitical, ideological divide that arises after the war and the tensions that continually threaten the passionate but tumultuous relationship between the film’s mismatched lovers. Poland’s submission to the Oscars this year, Cold War has just been shortlisted by the Motion Picture Academy — one of only ten foreign-language films to make the cut. It also just walked off with the European Film Awards for best film, director, screenplay and actress.

Loosely based on the stormy relationship between director Pawel Pawlikowski’s own parents (to whom the film is dedicated), the story opens in the Polish countryside where musician Wiktor (an intense, brooding Tomasz Kot) and ethnomusicologist Irena (Agata Kulesza) are on a government-sponsored quest to find and preserve the country’s cultural heritage. Those selected form the song-and-dance ensemble Mazurek (based on an actual Polish troupe called Mazowsze). One of those auditioning is Zula (a stunning turn by Joanna Kulig), whose strong voice, confident manner and sultry good looks catch Wiktor’s eye. The two begin a fraught but impassioned love affair. Zula is spontaneous, frank and impatient – the exact opposite of the calm, cautious, intellectual Wiktor.

The film, which covers a 15-year period, opens in 1946, as all of Europe is trying to recover from the horrors and physical destruction of World War II. The end of the conflict does not bring peace and prosperity to Eastern Europe the way it does to the West, however, as Stalin’s grip tightens over his newly expanded sphere of influence. Even Mazurek is expected to become a Communist propaganda tool. When Irena objects, she is forced out. Wiktor acquiesces, having already resolved to defect to the West in search of artistic freedom. He gets his opportunity when Mazurek, now a highly popular touring company, performs in East Germany. In the days before the Berlin Wall went up, defectors could simply walk into the Democratic Western sector of the city. Wiktor waits for Zula but she fails to show up at the designated spot. She is content in Poland, where she has achieved a measure of success she never dreamed possible. She doesn’t want to leave.

Tomasz goes to Paris, where he plays in a jazz club; Zula becomes the star of Mazurek. But the intensity of their amour fou never diminishes. Years pass without contact but they find ways to reunite, even if for just a day. They long for one another when apart but, once together, old conflicts emerge.

The film’s sensual, hypnotic look and feel derive in large measure from the heat generated by the two lead actors but also from the stark, shimmering black-and-white cinematography of Zal Lukasz, who also shot Pawlikowski’s previous movie, the Oscar-winning Ida (both pictures were shot in color and desaturated in post). “There was no color in Poland in the 1940s and 50s,” says the film’s director grimly. “It was all gray.” But the absence of color serves the film well, as contrast becomes one of the most important elements in the narrative, serving as a visual metaphor for the incendiary love that binds — and threatens to destroy — the couple.